Late-2000s recession

| Late 2000s recession |

|

Late 2000s recession in Africa |

| Part of a series on: |

| 2007–2010 financial crisis |

|---|

|

Major dimensions

|

|

Summits

|

|

Legislation

|

|

Company bailouts

|

|

Company failures

|

|

Causes

|

|

Solutions

|

The late-2000s recession (or the Great Recession[1][2][3][4]) is an economic recession that began in the United States in December 2007[5] as determined by the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research. It spread to much of the industrialized world, and has caused a pronounced deceleration of economic activity. This global recession has been taking place in an economic environment characterized by various imbalances and was sparked by the outbreak of the financial crisis of 2007–2010. Although the late-2000s recession has at times been referred to as "the Great Recession," this same phrase has been used to refer to every recession of the several preceding decades.[3] In July 2009, it was announced that a growing number of economists believed that the recession may have ended.[6][7] However, in the United States, the requisite two consecutive quarters of growth in the GDP did not actually occur until the end of 2009.

The financial crisis has been linked to reckless lending practices by financial institutions encouraged by the government and the growing trend of securitization of real estate mortgages in the United States.[8] The US mortgage-backed securities, which had risks that were hard to assess, were marketed around the world. A more broad based credit boom fed a global speculative bubble in real estate and equities, which served to reinforce the risky lending practices.[9][10] The precarious financial situation was made more difficult by a sharp increase in oil and food prices. The emergence of Sub-prime loan losses in 2007 began the crisis and exposed other risky loans and over-inflated asset prices. With loan losses mounting and the fall of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, a major panic broke out on the inter-bank loan market. As share and housing prices declined, many large and well established investment and commercial banks in the United States and Europe suffered huge losses and even faced bankruptcy, resulting in massive public financial assistance.

A global recession has resulted in a sharp drop in international trade, rising unemployment and slumping commodity prices. In December 2008, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) declared that the United States had been in recession since December 2007.[11] Several economists have predicted that recovery may not appear until 2011 and that the recession will be the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s.[12][13] The conditions leading up to the crisis, characterized by an exorbitant rise in asset prices and associated boom in economic demand, are considered a result of the extended period of easily available credit,[14] inadequate regulation and oversight,[15] or increasing inequality.[16]

The recession has renewed interest in Keynesian economic ideas on how to combat recessionary conditions. Fiscal and monetary policies have been significantly eased to stem the recession and financial risks. Economists advise that the stimulus should be withdrawn as soon as the economies recover enough to "chart a path to sustainable growth".[17][18][19]

Pre-recession economic imbalances

The onset of the economic crisis took most people by surprise. A 2009 paper identifies twelve economists and commentators who, between 2000 and 2006, predicted a recession based on the collapse of the then-booming housing market in the U.S:[20] Dean Baker, Wynne Godley, Fred Harrison, Michael Hudson, Eric Janszen, Steve Keen, Jakob Brøchner Madsen & Jens Kjaer Sørensen, Kurt Richebächer, Nouriel Roubini, Peter Schiff and Robert Shiller.[20]

Among the various imbalances in which the US monetary policy contributed by excessive money creation, leading to negative household savings and a huge US trade deficit, dollar volatility and public deficits, a focus can be made on the following ones:

Commodity boom

The decade of the 2000s saw a global explosion in prices, focused especially in commodities and housing, marking an end to the commodities recession of 1980–2000. In 2008, the prices of many commodities, notably oil and food, rose so high as to cause genuine economic damage, threatening stagflation and a reversal of globalization.[21]

In January 2008, oil prices surpassed $100 a barrel for the first time, the first of many price milestones to be passed in the course of the year.[22] In July 2008, oil peaked at $147.30[23] a barrel and a gallon of gasoline was more than $4 across most of the U.S.A. The economic contraction in the fourth quarter of 2008 caused a dramatic drop in demand and prices fell below $35 a barrel at the end of the year.[23] Some believe that this oil price spike was the product of Peak Oil.[24] There is concern that if the economy was to improve, oil prices might return to pre-recession levels.[25]

The food and fuel crises were both discussed at the 34th G8 summit in July 2008.[26]

Sulfuric acid (an important chemical commodity used in processes such as steel processing, copper production and bioethanol production) increased in price 3.5-fold in less than 1 year while producers of sodium hydroxide have declared force majeure due to flooding, precipitating similarly steep price increases.[27][28]

In the second half of 2008, the prices of most commodities fell dramatically on expectations of diminished demand in a world recession.[29]

Housing bubble

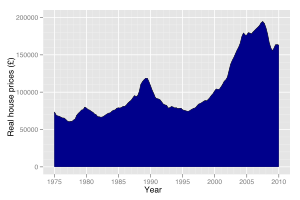

By 2007, real estate bubbles were still under way in many parts of the world,[30] especially in the United States, United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Spain, France, Poland,[31] South Africa, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Croatia,[32] Canada, Norway, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, Finland, Argentina,[33] Baltic states, India, Romania, Russia, Ukraine and China.[34] U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said in mid-2005 that "at a minimum, there's a little 'froth' (in the U.S. housing market) ... it's hard not to see that there are a lot of local bubbles".[35] The Economist magazine, writing at the same time, went further, saying "the worldwide rise in house prices is the biggest bubble in history".[36] Real estate bubbles are (by definition of the word "bubble") followed by a price decrease (also known as a housing price crash) that can result in many owners holding negative equity (a mortgage debt higher than the current value of the property).

Inflation

In February 2008, Reuters reported that global inflation was at historic levels, and that domestic inflation was at 10–20 year highs for many nations.[37] "Excess money supply around the globe, monetary easing by the Fed to tame financial crisis, growth surge supported by easy monetary policy in Asia, speculation in commodities, agricultural failure, rising cost of imports from China and rising demand of food and commodities in the fast growing emerging markets," have been named as possible reasons for the inflation.[38]

In mid-2007, IMF data indicated that inflation was highest in the oil-exporting countries, largely due to the unsterilized growth of foreign exchange reserves, the term "unsterilized" referring to a lack of monetary policy operations that could offset such a foreign exchange intervention in order to maintain a country's monetary policy target. However, inflation was also growing in countries classified by the IMF as "non-oil-exporting LDCs" (Least Developed Countries) and "Developing Asia", on account of the rise in oil and food prices.[39]

Inflation was also increasing in the developed countries,[40][41] but remained low compared to the developing world.

Causes

- Central banks' gold reserves – $0.845 tn.

- M0 (paper money) – - $3.9 tn.

- traditional (fractional reserve) banking assets – $39 tn.

- shadow banking assets – $62 tn.

- other assets – $290 tn.

- Bail-out money (early 2009) – $1.9 tn.

Debate over origins

The central debate about the origin has been focused on the respective parts played by the public monetary policy (in the US notably) and by private financial institutions practices.

On October 15, 2008, Anthony Faiola, Ellen Nakashima, and Jill Drew wrote a lengthy article in The Washington Post titled, "What Went Wrong".[43] In their investigation, the authors claim that former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, and SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt vehemently opposed any regulation of financial instruments known as derivatives. They further claim that Greenspan actively sought to undermine the office of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, specifically under the leadership of Brooksley E. Born, when the Commission sought to initiate regulation of derivatives. Ultimately, it was the collapse of a specific kind of derivative, the mortgage-backed security, that triggered the economic crisis of 2008.

While Greenspan's role as Chairman of the Federal Reserve has been widely discussed (the main point of controversy remains the lowering of Federal funds rate at only 1% for more than a year which, according to the Austrian School of economics, allowed huge amounts of "easy" credit-based money to be injected into the financial system and thus create an unsustainable economic boom),[44][45] there is also the argument that Greenspan actions in the years 2002–2004 were actually motivated by the need to take the U.S. economy out of the early 2000s recession caused by the bursting of the dot-com bubble — although by doing so he did not help avert the crisis, but only postpone it.[46][47]

Some economists- those of the Austrian school and those predicting the recession such as Steve Keen - claim that the ultimate point of origin of the great financial crisis of 2007–2010 can be traced back to an extremely indebted US economy. The collapse of the real estate market in 2006 was the close point of origin of the crisis. The failure rates of subprime mortgages were the first symptom of a credit boom tuned to bust and of a real estate shock. But large default rates on subprime mortgages cannot account for the severity of the crisis. Rather, low-quality mortgages acted as an accelerant to the fire that spread through the entire financial system. The latter had become fragile as a result of several factors that are unique to this crisis: the transfer of assets from the balance sheets of banks to the markets, the creation of complex and opaque assets, the failure of ratings agencies to properly assess the risk of such assets, and the application of fair value accounting. To these novel factors, one must add the now standard failure of regulators and supervisors in spotting and correcting the emerging weaknesses.[48]

Excessive Debt Levels as the Cause

In order to counter the Stock Market Crash of 2000 and the subsequent economic slowdown, the Federal Reserve eased credit availability and drove interest rates down to lows not seen in many decades. These low interest rates facilitated the growth of debt at all levels of the economy, chief among them private debt to purchase more expensive housing. High levels of debt have long been recognized as a causative factor for recessions.[49].

Any debt default has the possibility of causing the lender to also default, if the lender is itself in a weak financial condition and has too much debt. This second default in turn can lead to still further defaults through a domino effect. The chances of these followup defaults in increased at high levels of debt. Attempts to prevent this domino effect by bailing out Wall Street lenders such as AIG, Fannie May, and Freddie Mac have had mixed success. The takeover of Bear Stearns is another example of attempts to stop the dominoes from falling.[50]

Sub-prime lending as a cause

Based on the assumption that sub-prime lending precipitated the crisis, some have argued that the Clinton Administration may be partially to blame, while others have pointed to the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act by the 106th Congress, and over-leveraging by banks and investors eager to achieve high returns on capital.

Others take full credit for deregulating the Banking Industry. In November 1999, Phil Gramm, Republican Senator from Texas, took full credit for the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act with a Press Release from the Senate Banking and Finance Committee: "I am proud to be here because this is an important bill; it is a deregulatory bill. I believe that that is the wave of the future, and I am awfully proud to have been a part of making it a reality."

Some(who?) believe the roots of the crisis can be traced directly to sub-prime lending by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are government sponsored entities. The New York Times published an article that reported the Clinton Administration pushed for sub-prime lending: "Fannie Mae, the nation's biggest underwriter of home mortgages, has been under increasing pressure from the Clinton Administration to expand mortgage loans among low and moderate income people" (NYT, 30 September 1999).

In 1995, the administration also tinkered with Carter's Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 by regulating and strengthening the anti-redlining procedures. It is felt by many(who?) that this was done to help boost a stagnated home ownership figure that had hovered around 65% for many years. The result was a push by the administration for greater investment, by financial institutions, into riskier loans. In a 2000 United States Department of the Treasury study of lending trends for 305 cities from 1993 to 1998 it was shown that $467 billion of mortgage credit poured out of CRA-covered lenders into low- and mid-level income borrowers and neighborhoods. (See "The Community Reinvestment Act After Financial Modernization," April 2000.)

Government deregulation as a cause

In 1992, the 102nd Congress under the George H. W. Bush administration weakened regulation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with the goal of making available more money for the issuance of home loans. The Washington Post wrote: "Congress also wanted to free up money for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy mortgage loans and specified that the pair would be required to keep a much smaller share of their funds on hand than other financial institutions. Whereas banks that held $100 could spend $90 buying mortgage loans, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could spend $97.50 buying loans. Finally, Congress ordered that the companies be required to keep more capital as a cushion against losses if they invested in riskier securities. But the rule was never set during the Clinton administration, which came to office that winter, and was only put in place nine years later."[51]

Others have pointed to deregulation efforts as contributing to the collapse. In 1999, the 106th Congress, under Bill Clinton, passed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which repealed part of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. This repeal has been criticized by some for having contributed to the proliferation of the complex and opaque financial instruments which are at the heart of the crisis. However, some economists object to singling out the repeal of Glass-Steagall for criticism. Brad DeLong, a former advisor to President Clinton and economist at the University of California, Berkeley and Tyler Cowen of George Mason University have both argued that the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act softened the impact of the crisis by allowing for mergers and acquisitions of collapsing banks as the crisis unfolded in late 2008.[52]

Over-leveraging, credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations as causes

Another probable cause of the crisis—and a factor that unquestionably amplified its magnitude—was widespread miscalculation by banks and investors of the level of risk inherent in the unregulated Collateralized debt obligation and Credit Default Swap markets. Under this theory, banks and investors systematized the risk by taking advantage of low interest rates to borrow tremendous sums of money that they could only pay back if the housing market continued to increase in value.

According to an article published in Wired, the risk was further systematized by the use of David X. Li's Gaussian copula model function to rapidly price Collateralized debt obligations based on the price of related Credit Default Swaps.[53] Because it was highly tractable, it rapidly came to be used by a huge percentage of CDO and CDS investors, issuers, and rating agencies.[53] According to one wired.com article: "Then the model fell apart. Cracks started appearing early on, when financial markets began behaving in ways that users of Li's formula hadn't expected. The cracks became full-fledged canyons in 2008—when ruptures in the financial system's foundation swallowed up trillions of dollars and put the survival of the global banking system in serious peril...Li's Gaussian copula formula will go down in history as instrumental in causing the unfathomable losses that brought the world financial system to its knees."[53]

The pricing model for CDOs clearly did not reflect the level of risk they introduced into the system. It has been estimated that the "from late 2005 to the middle of 2007, around $450bn of CDO of ABS were issued, of which about one third were created from risky mortgage-backed bonds...[o]ut of that pile, around $305bn of the CDOs are now in a formal state of default, with the CDOs underwritten by Merrill Lynch accounting for the biggest pile of defaulted assets, followed by UBS and Citi."[54] The average recovery rate for high quality CDOs has been approximately 32 cents on the dollar, while the recovery rate for mezzanine CDO's has been approximately five cents for every dollar. These massive, practically unthinkable, losses have dramatically impacted the balance sheets of banks across the globe, leaving them with very little capital to continue operations.[54]

Credit creation as a cause

The Austrian School of Economics proposes that the crisis is an excellent example of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, in which credit created through the policies of central banking gives rise to an artificial boom, which is inevitably followed by a bust. This perspective argues that the monetary policy of central banks creates excessive quantities of cheap credit by setting interest rates below where they would be set by a free market. This easy availability of credit inspires a bundle of malinvestments, particularly on long term projects such as housing and capital assets, and also spurs a consumption boom as incentives to save are diminished. Thus an unsustainable boom arises, characterized by malinvestments and overconsumption.

But the created credit is not backed by any real savings nor is in response to any change in the real economy, hence, there are physically not enough resources to finance either the malinvestments or the consumption rate indefinitely. The bust occurs when investors collectively realize their mistake. This happens usually some time after interest rates rise again. The liquidation of the malinvestments and the consequent reduction in consumption throw the economy into a recession, whose severity mirrors the scale of the boom's excesses.

The Austrian School argues that the conditions previous to the crisis of the late 2000s correspond exactly to the scenario described above. The central bank of the United States, led by Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, kept interest rates very low for a long period of time to blunt the recession of the early 2000s. The resulting malinvestment and over-consumption of investors and consumers prompted the development of a housing bubble that ultimately burst, precipitating the financial crisis. This crisis, together with sudden and necessary deleveraging and cutbacks by consumers, businesses and banks, led to the recession. Austrian Economists argue further that while they probably affected the nature and severity of the crisis, factors such as a lack of regulation, the Community Reinvestment Act, and entities such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are insufficient by themselves to explain it.[55]

A positively sloped yield curve allows Primary Dealers (such as large investment banks) in the Federal Reserve system to fund themselves with cheap short term money while lending out at higher long-term rates. This strategy is profitable so long as the yield curve remains positively sloped. However, it creates a liquidity risk if the yield curve were to become inverted and banks would have to refund themselves at expensive short term rates while losing money on longer term loans.

The narrowing of the yield curve from 2004 and the inversion of the yield curve during 2007 resulted (with the expected 1 to 3 year delay) in a bursting of the housing bubble and a wild gyration of commodities prices as moneys flowed out of assets like housing or stocks and sought safe haven in commodities. The price of oil rose to over $140 dollars per barrel in 2008 before plunging as the financial crisis began to take hold in late 2008.

Other observers have doubted the role that the yield curve plays in controlling the business cycle. In a May 24, 2006 story CNN Money reported: "...in recent comments, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke repeated the view expressed by his predecessor Alan Greenspan that an inverted yield curve is no longer a good indicator of a recession ahead."

Oil prices

Economist James D. Hamilton has argued that the increase in oil prices in the period of 2007 through 2008 was a significant cause of the recession. He evaluated several different approaches to estimating the impact of oil price shocks on the economy, including some methods that had previously shown a decline in the relationship between oil price shocks and the overall economy. All of these methods "support a common conclusion; had there been no increase in oil prices between 2007:Q3 and 2008:Q2, the US economy would not have been in a recession over the period 2007:Q4 through 2008:Q3."[56] Hamilton's own model, a time-series econometric forecast based on data up to 2003, showed that the decline in GDP could have been successfully predicted to almost its full extent given knowledge of the price of oil. The results imply that oil prices were entirely responsible for the recession; however, Hamilton himself acknowledged that this was probably not the case but maintained that it showed that oil price increases made a significant contribution to the downturn in economic growth.[57]

Other claimed causes

Many libertarians, including Congressman and former 2008 Presidential candidate Ron Paul[58] and Peter Schiff in his book Crash Proof, claim to have predicted the crisis prior to its occurrence. Schiff also made a speech in 2006 in which he predicted the failure of Fannie and Freddie.[59] They are critical of theories that the free market caused the crisis[60] and instead argue that the Federal Reserve's expansionary monetary policy and the Community Reinvestment Act are the primary causes of the crisis.[61] Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve chairman, has said he was partially wrong to oppose regulation of the markets, and expressed "shocked disbelief" at the failure of self interest, alone, to manage risk in the markets.[62]

An empirical study by John B. Taylor concluded that the crisis was: (1) caused by excess monetary expansion; (2) prolonged by an inability to evaluate counter-party risk due to opaque financial statements; and (3) worsened by the unpredictable nature of government's response to the crisis.[63][64]

It has also been debated that the root cause of the crisis is overproduction of goods caused by globalization[65] (and especially vast investments in countries such as China and India by western multinational companies over the past 15–20 years, which greatly increased global industrial output at a reduced cost). Overproduction tends to cause deflation and signs of deflation were evident in October and November 2008, as commodity prices tumbled and the Federal Reserve was lowering its target rate to an all-time-low 0.25%.[66] On the other hand, Professor Herman Daly suggests that it is not actually an economic crisis, but rather a crisis of overgrowth beyond sustainable ecological limits.[67] This reflects a claim made in the 1972 book Limits to Growth, which stated that without major deviation from the policies followed in the 20th century, a permanent end of economic growth could be reached sometime in the first two decades of the 21st century, due to gradual depletion of natural resources.[68]

In laissez-faire capitalism, financial institutions would be risk-averse because failure would result in liquidation. But the Federal Reserve's 1984 rescue of Continental Illinois and the 1998 rescue of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund, among others, showed that institutions which failed to exercise due diligence could reasonably expect to be protected from the consequences of their mistakes. The belief that they could not be allowed to fail created a moral hazard which was a contributing factor to the late-2000s recession.[69]

Effects

Overview

The late-2000s recession is shaping up to be the worst post-World War II contraction on record:[70]

- Real gross domestic product (GDP) began contracting in the third quarter of 2008, and by early 2009 was falling at an annualized pace not seen since the 1950s.[71]

- Capital investment, which was in decline year-on-year since the final quarter of 2006, matched the 1957–58 post war record in the first quarter of 2009. The pace of collapse in residential investment picked up speed in the first quarter of 2009, dropping 23.2% year-on-year, nearly four percentage points faster than in the previous quarter.

- Domestic demand, in decline for five straight quarters, is still three months shy of the 1974–75 record, but the pace – down 2.6% per quarter vs. 1.9% in the earlier period – is a record-breaker already.

Trade and industrial production

In middle-October 2008, the Baltic Dry Index, a measure of shipping volume, fell by 50% in one week, as the credit crunch made it difficult for exporters to obtain letters of credit.[72]

In February 2009, The Economist claimed that the financial crisis had produced a "manufacturing crisis", with the strongest declines in industrial production occurring in export-based economies.[73]

In March 2009, Britain's Daily Telegraph reported the following declines in industrial output, from January 2008 to January 2009: Japan −31%, Korea −26%, Russia −16%, Brazil −15%, Italy −14%, Germany −12%.[74]

Some analysts even say the world is going through a period of deglobalization and protectionism after years of increasing economic integration.[75][76]

Sovereign funds and private buyers from the Middle East and Asia, including China,[77] are increasingly buying in on stakes of European and U.S. businesses, including industrial enterprises.[78] Due to the global recession they are available at a low price.[79][80] The Chinese government has concentrated on natural-resource deals across the world,[81] securing supplies of oil and minerals.[82]

Pollution

According to the International Energy Agency man-made greenhouse gas emissions will decrease by 3% in 2009, mainly as a result of the financial crisis. Previously emissions had been rising by around 3% per year. The drop in emissions is only the 4th to occur in 50 years.[83]

Unemployment

The International Labour Organization (ILO) predicted that at least 20 million jobs will have been lost by the end of 2009 due to the crisis — mostly in "construction, real estate, financial services, and the auto sector" — bringing world unemployment above 200 million for the first time.[84] The number of unemployed people worldwide could increase by more than 50 million in 2009 as the global recession intensifies, the ILO has forecast.[85]

In December 2007, the U.S. unemployment rate was 4.9%.[86] By October 2009, the unemployment rate had risen to 10.1%.[87] A broader measure of unemployment (taking into account marginally attached workers, those employed part time for economic reasons, and discouraged workers) was 16.3%.[88] In July 2009, fewer jobs were lost than expected, dipping the unemployment rate from 9.5% to 9.4%. Even fewer jobs were lost in August, 216,000, recorded as the lowest number of jobs since September 2008, but the unemployment rate rose to 9.7%. In October 2009, news reports announced that some employers who cut jobs due to the recession are beginning to hire them back. More recently, economists announced in January 2010 that economic growth in the U.S. resumed in the fourth quarter of 2009,[89] and some have predicted that limited job growth will begin in the spring of 2010.[90]

The average numbers for European Union nations are similar to the US ones. Some European countries have been hit by recession very hard, for instance Spain's unemployment rate reached 18.7% (37% for youths) in May 2009 — the highest in the eurozone.[91][92]

The rise of advanced economies in Brazil, India, and China increased the total global labor pool dramatically. Recent improvements in communication and education in these countries has allowed workers in these countries to compete more closely with workers in traditionally strong economies, such as the United States. This huge surge in labor supply has provided downward pressure on wages and contributed to unemployment.

Financial markets

For a time, major economies of the 21st century were believed to have begun a period of decreased volatility, which was sometimes dubbed The Great Moderation, because many economic variables appeared to have achieved relative stability. The return of commodity, stock market, and currency value volatility are regarded as indications that the concepts behind the Great Moderation were guided by false beliefs.[93]

January 2008 was an especially volatile month in world stock markets, with a surge in implied volatility measurements of the US-based S&P 500 index,[94] and a sharp decrease in non-U.S. stock market prices on Monday, January 21, 2008 (continuing to a lesser extent in some markets on January 22). Some headline writers and a general news columnist called January 21 "Black Monday" and referred to a "global shares crash,"[95][96] though the effects were quite different in different markets.

The effects of these events were also felt on the Shanghai Composite Index in China which lost 5.14 percent, most of this on financial stocks such as Ping An Insurance and China Life which lost 10 and 8.76 percent respectively.[97] Investors worried about the effect of a recession in the US economy would have on the Chinese economy. Citigroup estimates due to the number of exports from China to America a one percent drop in US economic growth would lead to a 1.3 percent drop in China's growth rate.

There were several large Monday declines in stock markets world wide during 2008, including one in January, one in August, one in September, and another in early October. As of October 2008, stocks in North America, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region had all fallen by about 30% since the beginning of the year.[98] The Dow Jones Industrial Average had fallen about 37% since January 2008.[99]

The simultaneous multiple crises affecting the US financial system in mid-September 2008 caused large falls in markets both in the US and elsewhere. Numerous indicators of risk and of investor fear (the TED spread, Treasury yields, the dollar value of gold) set records.[100]

Russian markets, already falling due to declining oil prices and political tensions with the West, fell over 10% in one day, leading to a suspension of trading,[101] while other emerging markets also exhibited losses.[102]

On September 18, UK regulators announced a temporary ban on short-selling of financial stocks.[103] On September 19 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) followed by placing a temporary ban of short-selling stocks of 799 specific financial institutions. In addition, the SEC made it easier for institutions to buy back shares of their institutions. The action is based on the view that short selling in a crisis market undermines confidence in financial institutions and erodes their stability.[104]

On September 22, the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) delayed opening by an hour[105] after a decision was made by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to ban all short selling on the ASX.[106] This was revised slightly a few days later.[107]

As is often the case in times of financial turmoil and loss of confidence, investors turned to assets which they perceived as tangible or sustainable. The price of gold rose by 30% from middle of 2007 to end of 2008. A further shift in investors' preference towards assets like precious metals[108] or land[109][110] is discussed in the media.

In March 2009, Blackstone Group CEO Stephen Schwarzman said that up to 45% of global wealth had been destroyed in little less than a year and a half.[111]

Travel

According to Zagat's 2009 U.S. Hotels, Resorts & Spas survey, business travel has decreased in the past year as a result of the recession. 30% of travelers surveyed stated they travel less for business today while only 21% of travelers stated that they travel more.[112] Reasons for the decline in business travel include company travel policy changes, personal economics, economic uncertainty and high airline prices. Hotels are responding to the downturn by dropping rates, ramping up promotions and negotiating deals for both business travelers and tourists.[112][113]

According to the World Tourism Organization, international travel suffered a strong slowdown beginning in June 2008,[114] and this declining trend intensified during 2009 resulting in a reduction from 922 million international tourist arrivals in 2008 to 880 million visitors in 2009, representing a worldwide decline of 4%, and an estimated 6% decline in international tourism receipts.[115] The decline caused by the recession was further exacerbated in some countries due to the outbreak of the AH1N1 virus.[115]

Insurance

A February 2009 study on the main British insurers showed that most of them do not plan to raise their insurance premiums for the year 2009, in spite of the prediction of a 20% raise made by The Daily Telegraph and The Daily Mirror. However, it is expected that the capital liquidity will become an issue and determine increases, having their capital tied up in investments yielding smaller dividends, corroborated with the £644 million underwriting losses suffered in 2007.[116]

Small-business lending

New York Times reported that the U.S. Treasury Department found a sizeable decrease in small-business lending by the 22 largest bank recipients of federal bailout money. The banks reduced their small-business lending by US$12.5 billion, a decline of 4.6 percent during a seven-month period ended in November 2009. During that time, the two biggest small-business lenders, Wells Fargo and Bank of America reduced their lending to small-business by 4.4 percent and 6.2 percent, respectively. Bank of America explained that about half of the decline was attributable to decrease demand, and a decline in sales and creditworthiness among small businesses furthered the drop.[117]

Countries most affected

The crisis affected all countries in some ways, but certain countries were vastly affected more than others. By measuring currency devaluation, equity market decline, and the rise in sovereign bond spreads, a picture of financial devastation emerges. Since these three indicators show financial weakness, taken together, they capture the impact of the crisis.[118] The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reports in its International Economics Bulletin that Ukraine, as well as Argentina and Jamaica, are the countries most deeply affected by the crisis.[118] Other severely affected countries are Ireland, Russia, Mexico, Hungary, the Baltic states, United States and United Kingdom. By contrast, China, Japan, India, Iran, Peru and Australia are "among the least affected."[118]

In December 2008, Greece experienced extensive civil unrest that continued into January and then again in late February many Greeks took part in a massive general strike because of the economic situation and shut down schools, airports, and many other services in Greece. In January 2009, the government leaders of Iceland were forced to call elections two years early after the people of Iceland staged mass protests and clashed with the police due to the government's handling of the economy.[119] Hundreds of thousands protested in France against President Sarkozy's economic policies, but it is important to remember that such protests, although rare in countries such as the USA, are quite a common phenomenon in Europe, even in periods of growth (major strikes in France in 1968, and many others occurring almost every five to ten years). Prompted by the financial crisis in Latvia, the opposition and trade unions there organized a rally against the cabinet of premier Ivars Godmanis on January 13, 2009. The rally gathered some 10–20 thousand people. In the evening, the rally turned into a riot. The crowd moved to the building of the parliament and attempted to force their way into it, but were repelled by the state's police. Police and protesters also clashed in Lithuania. In addition to various levels of unrest in Europe, Asian countries have also seen various degrees of protest. Communists and others rallied in Moscow to protest the Russian government's economic plans. Protests have also occurred in China as demands from the West for exports were dramatically reduced and unemployment increased.

Beginning February 26, 2009, an Economic Intelligence Briefing was added to the daily intelligence briefings prepared for the President of the United States. This addition reflected the assessment of United States intelligence agencies that the global financial crisis presented a serious threat to international stability.[120] In March 2009, British think tank Economist Intelligence Unit published a special report titled 'Manning the barricades' in which it estimated "who's at risk as deepening economic distress foments social unrest". The Report envisioned the next two years filled with great social upheavals, disrupted economies and toppled governments around the globe.[121]

Business Week in March 2009 stated that global political instability is rising fast due to the global financial crisis and is creating new challenges that need managing.[122] The Associated Press reported in March 2009 that: United States "Director of National Intelligence Dennis Blair has said the economic weakness could lead to political instability in many developing nations."[123] Even some developed countries are seeing political instability.[119] NPR reports that David Gordon, a former intelligence officer who now leads research at the Eurasia Group, said: "Many, if not most, of the big countries out there have room to accommodate economic downturns without having large-scale political instability if we're in a recession of normal length. If you're in a much longer-run downturn, then all bets are off."[124]

- "The recent wave of popular unrest was not confined to Eastern Europe. Ireland, Iceland, France, the U.K. and Greece also experienced street protests, but many Eastern European governments seem more vulnerable as they have limited policy options to address the crisis and little or no room for fiscal stimulus due to budgetary or financing constrains. Deeply unpopular austerity measures, including slashed public wages, tax hikes and curbs on social spending will keep fanning public discontent in the Baltic states, Hungary and Romania. Dissatisfaction linked to the economic woes will be amplified in the countries where governments have been weakened by high-profile corruption and fraud scandals (Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Romania, the UK and Bulgaria)."[125]

Policy responses

The financial phase of the crisis led to emergency interventions in many national financial systems. As the crisis developed into genuine recession in many major economies, economic stimulus meant to revive economic growth became the most common policy tool. After having implemented rescue plans for the banking system, major developed and emerging countries announced plans to relieve their economies. In particular, economic stimulus plans were announced in China, the United States, and the European Union.[126] Bailouts of failing or threatened businesses were carried out or discussed in the USA, the EU, and India.[127] In the final quarter of 2008, the financial crisis saw the G-20 group of major economies assume a new significance as a focus of economic and financial crisis management.

United States policy responses

The Federal Reserve, Treasury, and Securities and Exchange Commission took several steps on September 19 to intervene in the crisis. To stop the potential run on money market mutual funds, the Treasury also announced on September 19 a new $50 billion program to insure the investments, similar to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) program.[128] Part of the announcements included temporary exceptions to section 23A and 23B (Regulation W), allowing financial groups to more easily share funds within their group. The exceptions would expire on January 30, 2009, unless extended by the Federal Reserve Board.[129] The Securities and Exchange Commission announced termination of short-selling of 799 financial stocks, as well as action against naked short selling, as part of its reaction to the mortgage crisis.[130]

Market volatility within US 401(k) and retirement plans

The US Pension Protection Act of 2006 included a provision which changed the definition of Qualified Default Investments (QDI) for retirement plans from stable value investments, money market funds, and cash investments to investments which expose an individual to appropriate levels of stock and bond risk based on the years left to retirement. The Act required that Plan Sponsors move the assets of individuals who had never actively elected their investments and had their contributions in the default investment option. This meant that individuals who had defaulted into a cash fund with little fluctuation or growth would soon have their account balances moved to much more aggressive investments.

Starting in early 2008, most US employer-sponsored plans sent notices to their employees informing them that the plan default investment was changing from a cash/stable option to something new, such as a retirement date fund which had significant market exposure. Most participants ignored these notices until September and October, when the market crash was on every news station and media outlet. It was then that participants called their 401(k) and retirement plan providers and discovered losses in excess of 30% in some cases. Call centers for 401(k) providers experienced record call volume and wait times, as millions of inexperienced investors struggled to understand how their investments had been changed so fundamentally without their explicit consent, and reacted in a panic by liquidating everything with any stock or bond exposure, locking in huge losses in their accounts.

Due to the speculation and uncertainty in the market, discussion forums filled with questions about whether or not to liquidate assets[131] and financial gurus were swamped with questions about the right steps to take to protect what remained of their retirement accounts. During the third quarter of 2008, over $72 billion left mutual fund investments that invested in stocks or bonds and rushed into Stable Value investments in the month of October.[132] Against the advice of financial experts, and ignoring historical data illustrating that long-term balanced investing has produced positive returns in all types of markets,[133] investors with decades to retirement instead sold their holdings during one of the largest drops in stock market history.

Loans to banks for asset-backed commercial paper

During the week ending September 19, 2008, money market mutual funds had begun to experience significant withdrawals of funds by investors. This created a significant risk because money market funds are integral to the ongoing financing of corporations of all types. Individual investors lend money to money market funds, which then provide the funds to corporations in exchange for corporate short-term securities called asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP). However, a potential bank run had begun on certain money market funds. If this situation had worsened, the ability of major corporations to secure needed short-term financing through ABCP issuance would have been significantly affected. To assist with liquidity throughout the system, the US Treasury and Federal Reserve Bank announced that banks could obtain funds via the Federal Reserve's Discount Window using ABCP as collateral.[128][134]

Federal Reserve lowers interest rates

| Federal reserve rates changes (Just data after January 1, 2008 ) | |||||

| Date | Discount rate | Discount rate | Discount rate | Fed funds | Fed funds rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | ||||

| rate change | new interest rate | new interest rate | rate change | new interest rate | |

| October 8, 2008* | -0.50% | 1.75% | 2.25% | -0.50% | 1.50% |

| April 30, 2008 | -0.25% | 2.25% | 2.75% | -.25% | 2.00% |

| March 18, 2008 | -0.75% | 2.50% | 3.00% | -0.75% | 2.25% |

| March 16, 2008 | -.025% | 3.25% | 3.75% | ||

| January 30, 2008 | -0.50% | 3.50% | 4.00% | -0.50% | 3.00% |

| January 22, 2008 | -0.75% | 4.00% | 4.50% | -.075% | 3.50% |

– * Part of a coordinated global rate cut of 50 basis point by main central banks.[135]

– See more detailed US federal discount rate chart:[136]

Legislation

The Secretary of the United States Treasury, Henry Paulson and President George W. Bush proposed legislation for the government to purchase up to US$700 billion of "troubled mortgage-related assets" from financial firms in hopes of improving confidence in the mortgage-backed securities markets and the financial firms participating in it.[137] Discussion, hearings and meetings among legislative leaders and the administration later made clear that the proposal would undergo significant change before it could be approved by Congress.[138] On October 1, a revised compromise version was approved by the Senate with a 74–25 vote. The bill, HR1424 was passed by the House on October 3, 2008 and signed into law. The first half of the bailout money was primarily used to buy preferred stock in banks instead of troubled mortgage assets.[139]

In January 2009, the Obama administration announced a stimulus plan to revive the economy with the intention to create or save more than 3.6 million jobs in two years. The cost of this initial recovery plan was estimated at 825 billion dollars (5.8% of GDP). The plan included 365.5 billion dollars to be spent on major policy and reform of the health system, 275 billion (through tax rebates) to be redistributed to households and firms, notably those investing in renewable energy, 94 billion to be dedicated to social assistance for the unemployed and families, 87 billion of direct assistance to states to help them finance health expenditures of Medicaid, and finally 13 billion spent to improve access to digital technologies. The administration also attributed of 13.4 billion dollars aid to automobile manufacturers General Motors and Chrysler, but this plan is not included in the stimulus plan.

These plans are meant to abate further economic contraction, however, with the present economic conditions differing from past recessions, in, that, many tenets of the American economy such as manufacturing, textiles, and technological development have been outsourced to other countries. Public works projects associated with the economic recovery plan outlined by the Obama Administration have been degraded by the lack of road and bridge development projects that were highly abundant in the Great Depression but are now mostly constructed and are mostly in need of maintenance. Regulations to establish market stability and confidence have been neglected in the Obama plan and have yet to be incorporated.

Federal Reserve response

In an effort to increase available funds for commercial banks and lower the fed funds rate, on September 29 the U.S. Federal Reserve announced plans to double its Term Auction Facility to $300 billion. Because there appeared to be a shortage of U.S. dollars in Europe at that time, the Federal Reserve also announced it would increase its swap facilities with foreign central banks from $290 billion to $620 billion.[140]

As of December 24, 2008, the Federal Reserve had used its independent authority to spend $1.2 trillion on purchasing various financial assets and making emergency loans to address the financial crisis, above and beyond the $700 billion authorized by Congress from the federal budget. This includes emergency loans to banks, credit card companies, and general businesses, temporary swaps of treasury bills for mortgage-backed securities, the sale of Bear Stearns, and the bailouts of American International Group (AIG), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and Citigroup.[141]

Asia-Pacific policy responses

On September 15, 2008 China cut its interest rate for the first time since 2002. Indonesia reduced its overnight repo rate, at which commercial banks can borrow overnight funds from the central bank, by two percentage points to 10.25 percent. The Reserve Bank of Australia injected nearly $1.5 billion into the banking system, nearly three times as much as the market's estimated requirement. The Reserve Bank of India added almost $1.32 billion, through a refinance operation, its biggest in at least a month.[142] On November 9, 2008 the 2008 Chinese economic stimulus plan is a RMB¥ 4 trillion ($586 billion) stimulus package announced by the central government of the People's Republic of China in its biggest move to stop the global financial crisis from hitting the world's third largest economy. A statement on the government's website said the State Council had approved a plan to invest 4 trillion yuan ($586 billion) in infrastructure and social welfare by the end of 2010. The stimulus package will be invested in key areas such as housing, rural infrastructure, transportation, health and education, environment, industry, disaster rebuilding, income-building, tax cuts, and finance.

China's export driven economy is starting to feel the impact of the economic slowdown in the United States and Europe, and the government has already cut key interest rates three times in less than two months in a bid to spur economic expansion. On November 28, 2008, the Ministry of Finance of the People's Republic of China and the State Administration of Taxation jointly announced a rise in export tax rebate rates on some labor-intensive goods. These additional tax rebates will take place on December 1, 2008.[143]

The stimulus package was welcomed by world leaders and analysts as larger than expected and a sign that by boosting its own economy, China is helping to stabilize the global economy. News of the announcement of the stimulus package sent markets up across the world. However, Marc Faber January 16 said that China according to him was in recession.

In Taiwan, the central bank on September 16, 2008 said it would cut its required reserve ratios for the first time in eight years. The central bank added $3.59 billion into the foreign-currency interbank market the same day. Bank of Japan pumped $29.3 billion into the financial system on September 17, 2008 and the Reserve Bank of Australia added $3.45 billion the same day.[144]

In developing and emerging economies, responses to the global crisis mainly consisted in low-rates monetary policy (Asia and the Middle East mainly) coupled with the depreciation of the currency against the dollar. There were also stimulus plans in some Asian countries, in the Middle East and in Argentina. In Asia, plans generally amounted to 1 to 3% of GDP, with the notable exception of China, which announced a plan accounting for 16% of GDP (6% of GDP per year).

European policy responses

Until September 2008, European policy measures were limited to a small number of countries (Spain and Italy). In both countries, the measures were dedicated to households (tax rebates) reform of the taxation system to support specific sectors such as housing. From September, as the financial crisis began to seriously affect the economy, many countries announced specific measures: Germany, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Sweden. The European Commission proposed a €200 billion stimulus plan to be implemented at the European level by the countries. At the beginning of 2009, the UK and Spain completed their initial plans, while Germany announced a new plan.

The European Central Bank injected $99.8 billion in a one-day money-market auction. The Bank of England pumped in $36 billion. Altogether, central banks throughout the world added more than $200 billion from the beginning of the week to September 17.[144]

On September 29, 2008 the Belgian, Luxembourg and Dutch authorities partially nationalized Fortis. The German government bailed out Hypo Real Estate.

On 8 October 2008 the British Government announced a bank rescue package of around £500 billion[145] ($850 billion at the time). The plan comprises three parts. First, £200 billion will be made available to the banks in the Bank of England's Special Liquidity scheme. Second, the Government will increase the banks' market capitalization, through the Bank Recapitalization Fund, with an initial £25 billion and another £25 billion to be provided if needed. Third, the Government will temporarily underwrite any eligible lending between British banks up to around £250 billion. In February 2009 Sir David Walker was appointed to lead a government inquiry into the corporate governance of banks.

In early December German Finance Minister Peer Steinbrück indicated that he does not believe in a "Great Rescue Plan" and indicated reluctance to spend more money addressing the crisis.[146] In March 2009, The European Union Presidency confirms that the EU is strongly resisting the US pressure to increase European budget deficits.[147]

Global responses

Most political responses to the economic and financial crisis has been taken, as seen above, by individual nations. Some coordination took place at the European level, but the need to cooperate at the global level has led leaders to activate the G-20 major economies entity. A first summit dedicated to the crisis took place, at the Heads of state level in November 2008 (2008 G-20 Washington summit).

The G-20 countries met in a summit held on November 2008 in Washington to address the economic crisis. Apart from proposals on international financial regulation, they pledged to take measures to support their economy and to coordinate them, and refused any resort to protectionism.

Another G-20 summit was held in London on April 2009. Finance ministers and central banks leaders of the G-20 met in Horsham on March to prepare the summit, and pledged to restore global growth as soon as possible. They decided to coordinate their actions and to stimulate demand and employment. They also pledged to fight against all forms of protectionism and to maintain trade and foreign investments. They also committed to maintain the supply of credit by providing more liquidity and recapitalizing the banking system, and to implement rapidly the stimulus plans. As for central bankers, they pledged to maintain low-rates policies as long as necessary. Finally, the leaders decided to help emerging and developing countries, through a strengthening of the IMF.

Countries maintaining growth or technically avoiding recession

Poland is the only member of the European Union to have avoided a decline in GDP, meaning that in 2009 Poland has created the most GDP growth in the EU. As of December 2009 the Polish economy had not entered recession nor even contracted, while its IMF 2010 GDP growth forecast of 1.9 per cent is expected to be upgraded.[148][149][150] Analysts have identified several causes: Extremely low levels of bank lending and a relatively very small mortgage market; the relatively recent dismantling of EU trade barriers and the resulting surge in demand for Polish goods since 2004; the receipt of direct EU funding since 2004; lack of over-dependence on a single export sector; a tradition of government fiscal responsibility; a relatively large internal market; the free-floating Polish zloty; low labour costs attracting continued foreign direct investment; economic difficulties at the start of the decade which prompted austerity measures in advance of the world crisis; a government decision to refrain from quantative easing.

While China, India and Iran have experienced slowing growth, they have not entered recession.

South Korea narrowly avoided technical recession in the first quarter of 2009.[151] The International Energy Agency stated in mid September that South Korea could be the only large OECD country to avoid recession for the whole of 2009.[152] It was the only developed economy to expand in the first half of 2009. On October 6, Australia became the first G20 country to raise its main interest rate, with the Reserve Bank of Australia deciding to move rates up to 3.25% from 3.00%.[153]

Australia has avoided a technical recession after experiencing only one quarter of negative growth in the fourth quarter of 2008, with GDP returning to positive in the first quarter of 2009.[154][155]

Countries in economic recession or depression

Many countries experienced recession in 2008.[156] The countries/territories currently in a technical recession are Estonia, Latvia, Ireland, New Zealand, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Italy, Russia and Germany.

Denmark went into recession in the first quarter of 2008, but came out again in the second quarter.[157] Iceland fell into an economic depression in 2008 following the collapse of its banking system. (see Icelandic financial crisis)

The following countries went into recession in the second quarter of 2008: Estonia,[158] Latvia,[159] Ireland[160] and New Zealand.[161]

The following countries/territories went into recession in the third quarter of 2008: Japan,[162] Sweden,[163] Hong Kong,[164] Singapore,[165] Italy,[166] Turkey[156] and Germany.[167] As a whole the fifteen nations in the European Union that use the euro went into recession in the third quarter,[168] and the United Kingdom. In addition, the European Union, the G7, and the OECD all experienced negative growth in the third quarter.[156]

The following countries/territories went into technical recession in the fourth quarter of 2008: United States, Switzerland,[169] Spain,[170] and Taiwan.[171]

South Korea "miraculously" avoided recession with GDP returning positive at a 0.1% expansion in the first quarter of 2009.[172]

Of the seven largest economies in the world by GDP, only China and France avoided a recession in 2008. France experienced a 0.3% contraction in Q2 and 0.1% growth in Q3 of 2008. In the year to the third quarter of 2008 China grew by 9%. This is interesting as China has until recently considered 8% GDP growth to be required simply to create enough jobs for rural people moving to urban centres.[173] This figure may more accurately be considered to be 5–7% now that the main growth in working population is receding. Growth of between 5%–8% could well have the type of effect in China that a recession has elsewhere. Ukraine went into technical depression in January 2009 with a nominal annualized GDP growth of −20%.[174]

The recession in Japan intensified in the fourth quarter of 2008 with a nominal annualized GDP growth of −12.7%,[175] and deepened further in the first quarter of 2009 with a nominal annualized GDP growth of −15.2%.[176]

Official forecasts in parts of the world

On March 2009, U.S. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said in an interview that he felt that if banks began lending more freely, allowing the financial markets to return to normal, the recession could end during 2009.[7][177] In that same interview, Bernanke said Green shoots of economic revival are already evident.[178] On February 18, 2009, the US Federal Reserve cut their economic forecast of 2009, expecting the US output to shrink between 0.5% and 1.5%, down from its forecast in October 2008 of output between +1.1% (growth) and −0.2% (contraction).[179]

The EU commission in Brussels updated their earlier predictions on January 19, 2009, expecting Germany to contract −2.25% and −1.8% on average for the 27 EU countries.[180] According to new forecasts by Deutsche Bank (end of November 2008), the economy of Germany will contract by more than 4% in 2009.[181]

On November 3, 2008, according to all newspapers, the European Commission in Brussels predicted for 2009 only an extremely low increase by 0.1% of the GDP, for the countries of the Euro zone (France, Germany, Italy, etc.).[182] They also predicted negative numbers for the UK (−1.0%), Ireland, Spain, and other countries of the EU. Three days later, the IMF at Washington, D.C., predicted for 2009 a worldwide decrease, −0.3%, of the same number, on average over the developed economies (−0.7% for the US, and −0.8% for Germany).[183] On April 22, 2009, the German ministers of finance and that of economy, in a common press conference, corrected again their numbers for 2009 downwards: this time the "prognosis" for Germany was a decrease of the GDP of at least −5%,[184] in agreement with a recent prediction of the IMF.[185]

On June 11, 2009, the World Bank Group predicted for 2009 for the first time a global contraction of the economic power, precisely by −3%.[186]

Comparisons with the Great Depression

Although some casual comparisons between the late-2000s recession and the Great Depression have been made, there remain large differences between the two events.[187][188][189] The consensus among economists in March 2009 was that a depression was not likely to occur.[190] UCLA Anderson Forecast director Edward Leamer said on March 25, 2009 that there had not been any major predictions at that time which resembled a second Great Depression:

"We've frightened consumers to the point where they imagine there is a good prospect of a Great Depression. That certainly is not in the prospect. No reputable forecaster is producing anything like a Great Depression."[191]

Differences explicitly pointed out between the recession and the Great Depression include the facts that over the 79 years between 1929 and 2008, great changes occurred in economic philosophy and policy,[192] the stock market had not fallen as far as it did in 1932 or 1982, the 10-year price-to-earnings ratio of stocks was not as low as in the '30s or '80s, inflation-adjusted U.S. housing prices in March 2009 were higher than any time since 1890 (including the housing booms of the 1970s and '80s),[193] the recession of the early '30s lasted over three-and-a-half years,[192] and during the 1930s the supply of money (currency plus demand deposits) fell by 25% (where as in 2008 and 2009 the Fed "has taken an ultraloose credit stance").[194] Furthermore, the unemployment rate in 2008 and early 2009 and the rate at which it rose was comparable to most of the recessions occurring after World War II, and was dwarfed by the 25% unemployment rate peak of the Great Depression.[192]

Price-to-earnings ratios have yet to drop as low as in previous recessions. On this issue, "it is critically important, though, to recognize that different analysts have different earnings expectations, and the consensus view is more often wrong than right."[195] Some argue that price-to-earnings ratios remain high because of unprecedented falls in earnings.[196]

Three years into the Great Depression, unemployment reached a peak of 25% in the U.S.[197] The United States entered into recession in December 2007[198] and in March 2009, U-3 unemployment reached 8.5%.[199] In March 2009, statistician[200] John Williams "argue[d] that measurement changes implemented over the years make it impossible to compare the current unemployment rate with that seen during the Great Depression".[200]

Nobel Prize winning Economist Paul Krugman predicted a series of depressions in his Return to Depression Economics (2000), based on "failures on the demand side of the economy." On January 5, 2009, he wrote that "preventing depressions isn't that easy after all" and that "the economy is still in free fall."[201] In March 2009, Krugman explained that a major difference in this situation is that the causes of this financial crisis were from the shadow banking system. "The crisis hasn't involved problems with deregulated institutions that took new risks... Instead, it involved risks taken by institutions that were never regulated in the first place."[202]

On February 22, NYU economics professor Nouriel Roubini said that the crisis was the worst since the Great Depression, and that without cooperation between political parties and foreign countries, and if poor fiscal policy decisions (such as support of zombie banks) are pursued, the situation "could become as bad as the Great Depression."[203] On April 27, 2009, Roubini expressed a more upbeat assessment by noting that "the bottom of the economy [will be seen] toward the beginning or middle of next year."[204]

Market strategist Phil Dow "said he believes distinctions exist between the current market malaise" and the Great Depression. The Dow's fall of over 50% in 17 months is similar to a 54.7% fall in the Great Depression, followed by a total drop of 89% over the next 16 months. "It's very troubling if you have a mirror image," said Dow.[205] Floyd Norris, chief financial correspondent of The New York Times, wrote in a blog entry in March 2009 that the decline has not been a mirror image of the Great Depression, explaining that although the decline amounts were nearly the same at the time, the rates of decline had started much faster in 2007, and that the past year had only ranked eighth among the worst recorded years of percentage drops in the Dow. The past two years ranked third however.[206]

On November 15, 2008, author and SMU economics professor Ravi Batra said he is "afraid the global financial debacle will turn into a steep recession and be the worst since the Great Depression, even worse than the painful slump of 1980–1982 that afflicted the whole world".[207] In 1978, Batra's book The Downfall of Capitalism and Communism was published. His first major prediction came true with the collapse of Soviet Communism in 1990. His second major prediction for a financial crisis to engulf the capitalist system seems to be unfolding since 2007 with increasing attention being paid to his work.[208][209][210]

In his final press conference as president, George W. Bush claimed that in September 2008 his chief economic advisors had said that the economic situation could at some point become worse than the Great Depression.[211]

A tent city in Sacramento, California was described as "images, hauntingly reminiscent of the iconic photos of the 1930s and the Great Depression" and "evocative Depression-era images."[212]

On April 6, 2009 Vernon L. Smith and Steven Gjerstad offered the hypothesis "that a financial crisis that originates in consumer debt, especially consumer debt concentrated at the low end of the wealth and income distribution, can be transmitted quickly and forcefully into the financial system. It appears that we're witnessing the second great consumer debt crash, the end of a massive consumption binge."[213]

On April 17, 2009, head of the IMF Dominique Strauss-Kahn said that there was a chance that certain countries may not implement the proper policies to avoid feedback mechanisms that could eventually turn the recession into a depression. "The free-fall in the global economy may be starting to abate, with a recovery emerging in 2010, but this depends crucially on the right policies being adopted today." The IMF pointed out that unlike the Great Depression, this recession was synchronized by global integration of markets. Such synchronized recessions were explained to last longer than typical economic downturns and have slower recoveries.[214]

In South Africa

On February 11, South Africa's Finance Minister Trevor Manuel said that "what started as a financial crisis might well become a second Great Depression."[215]

In the United Kingdom

On February 10, 2009, Ed Balls, Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families of the United Kingdom, said that "I think that this is a financial crisis more extreme and more serious than that of the 1930s and we all remember how the politics of that era were shaped by the economy."[216] On January 24, 2009, Edmund Conway, Economics Editor for The Daily Telegraph, wrote that "The plight facing Britain is uncannily similar to the 1930s, since prices of many assets – from shares to house prices – are falling at record rates [in Britain], but the value of the debt against which they are held remains unchanged."[217]

In Ireland

The Republic of Ireland "technically" entered into an economic depression in 2009.[218] The ESRI (Economic and Social Research Institute) predict an economic contraction of 14% by 2010,[219] however this number may have already been exceeded with GDP dropping 7.1% quarter on quarter during the fourth quarter of 2008,[220] and a possible greater contraction in the first quarter of 2009 with the fall in all OECD countries with the exception of France exceeding the drop of the previous quarter.[221] Unemployment is up 8.75%[222] to 11.4%.[223][224][225] Government borrowing and the financial bailout and Nationalisation of one of Ireland's banks[226] which were loaded with debt due to the Irish property bubble.

Job losses and unemployment rates

Many jobs have been lost worldwide. In the US, job loss has been going on since December 2007, and it accelerated drastically starting in September 2008 following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers.[227] By February 2010, the American economy is reported to be more shaky than the economy of Canada. Many service industries have reported dropping their prices in order to maximize profit margins in an era where employment is fleeting and either underemployment on unemployment is a sure factor in life.

Net job gains and losses by month in the United States

- September 2008 – 280,000 jobs lost

- October 2008 – 240,000 jobs lost

- November 2008 – 333,000 jobs lost

- December 2008 – 632,000 jobs lost[228]

- January 2009 – 741,000 jobs lost

- February 2009 – 681,000 jobs lost

- March 2009 – 652,000 jobs lost

- April 2009 – 519,000 jobs lost

- May 2009 – 303,000 jobs lost

- June 2009 – 463,000 jobs lost

- July 2009 – 276,000 jobs lost

- August 2009 – 201,000 jobs lost

- September 2009 – 263,000 jobs lost

- October 2009 – 111,000 jobs lost[229]

- November 2009 - 64,000 jobs created[230]

- December 2009 - 109,000 jobs lost[230]

- January 2010 - 14,000 jobs created[230]

- February 2010 - 39,000 jobs created

- March 2010 - 208,000 jobs created

- April 2010 - 290,000 jobs created

- May 2010 - 413,000 jobs created

- June 2010 - 125,000 Federal Census jobs lost, 31,000 private sector jobs created

- July 2010 - 131,000 Federal Census jobs lost, 71,000 private sector jobs created

- 2008 (September 2008 – December 2008) – 2.6 million jobs lost

- 2009 (January 2009 – December 2009) – 4.2 million jobs lost[231]

- 2010 (January 2010–present) - Approximately 600,000 jobs created

- Current unemployment rate: 9.5%

Since the start of 2008, 6.7 million jobs have been lost, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.[232]

Canada net job losses and gains by month

Drastic job loss in Canada started later than in the US. Some months in 2008 had job growth, such as September, while others such as July had losses. Due to the collapse of the American car industry at the same time as a strong Canadian dollar achieved parity +10% against a poorly-performing US dollar, the cross-border manufacturing industry has been disproportionately affected throughout.[233]

- September 2008 – No net loss

- October 2008 – No net loss

- November 2008 – 71,000 jobs lost[234]

- December 2008 – 34,000 jobs lost

- January 2009 – 129,000 jobs lost

- February 2009 – 82,600 jobs lost[235]

- March 2009 – 61,300 jobs lost

- April 2009 – No net loss (1)

- May 2009 – 36,000 jobs lost

- October 2009 – 43,200 jobs lost

- December 2009 - 28,300 jobs lost[236]

- January 2010 - 43,000 jobs created[237]

- February 2010 - 21,000 jobs created[238]

- March 2010 - 17,900 jobs created[239]

- April 2010 - 109,000 jobs created[240]

- May 2010 - 25,000 jobs created[241]

- June 2010 - 20,000 jobs created[242]

(1) 37,000 jobs are gained in the self-employment category[243]

While job creation has increased in the past three months, most Canadians still complain about people getting laid off from work. However, a growing amount of these layoffs are considered for seasonal purposes and has little or no relation to the recession. Excluding Stelco employees, most laid off workers have six months to acquire a job while collecting unemployment insurance. After that, they must go on welfare and continue their job search from there.

- May 2009 Canadian unemployment rate: 8.4%

- September 2009 Canadian unemployment rate: 8.7%

- November 2009 Canadian unemployment rate: 8.6%[244]

- January 2010 Canadian unemployment rate: 8.3%

- May 2010 Canadian unemployment rate: 8.1%

- June 2010 Canadian unemployment rate: 8.1%[237]

The unemployment rate has been stabilized between 8.0% and 11.0% for the past two years; signifying the economic strength of Canada's financial institutions compared to its counterparts in the United States. Many job places in Canada have opted to reduce hours rather than lay off staff - especially in industries that are needed to keep the economy from going into a depression. While the automotive sector is slowly recalling workers back to work, grocery stores and restaurants have slashed hours in the face of the global recession.

Australia net job losses and gains by month

- September 2008 – 2,200 jobs created

- October 2008 – 34,300 jobs created

- November 2008 – 15,600 jobs lost

- December 2008 – 1,200 jobs lost

- January 2009 – 1,200 jobs created

- February 2009 – 1,800 jobs created

- March 2009 – 34,700 jobs lost

- April 2009 – 27,300 jobs created

- May 2009 – 1,700 jobs lost

- June 2009 – 21,400 jobs lost

- July 2009 – 32,200 jobs created

- August 2009 – 27,100 jobs lost

- September 2009 – 40,600 jobs created

- October 2009 – 24,500 jobs created

April 2009 Australian unemployment rate: 5.5%[245]

July 2009 Australian unemployment rate: 5.8%[246]

August 2009 Australian unemployment rate: 5.8%[247]

September 2009 Australian unemployment rate: 5.7%[248]

October 2009 Australian unemployment rate: 5.8%[249]

The unemployment rate for October rose slightly due to population growth and other factors leading to 35,000 people looking for work, even though 24,500 jobs were created.

In general, throughout the subdued economic growth caused by the recession in the rest of the world, Australian employers have elected to cut working hours rather than fire employees, in recognition of the skill shortage caused by the resources boom.

See also

- 2008 Chinese economic stimulus plan

- 2008 United States bank failures

- 2008–2009 Keynesian resurgence

- 2008–2009 Latvian financial crisis

- 2008–2009 Russian financial crisis

- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

- Automotive industry crisis of 2008–2009

- Bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers

- Bear Stearns subprime mortgage hedge fund crisis

- Federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

- Financial crisis of 2007–2010

- Great Depression

- List of entities involved in 2007–2008 financial crises

- Statistical Arbitrage Events of summer 2007

- Subprime crisis impact timeline

- United States bear market of 2007–2009

- United States housing bubble

- United States housing market correction

- 2000s commodities boom

References

- ↑ Rampell, Catherine (2010-07-30). The New York Times. http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/30/the-great-recession-earns-its-title/?scp=2&sq=the%20great%20recession&st=cse.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Mortimer (2010-01-21). "Mortimer Zuckerman: The Great Recession Continues - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703837004575013592466508822.html. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rampell, Catherine (11 March 2009), "'Great Recession': A Brief Etymology", The New York Times, http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/03/11/great-recession-a-brief-etymology/

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (2010-07-04). "With the US trapped in depression, this really is starting to feel like 1932". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/ambroseevans_pritchard/7871421/With-the-US-trapped-in-depression-this-really-is-starting-to-feel-like-1932.html.

- ↑ Mark Hulbert (July 15, 2010). "It's Dippy to Fret About a Double-Dip Recession". http://online.barrons.com/article/SB50001424052970203983104575367471896032724.html?mod=googlenews_barrons.

- ↑ Daniel Gross, The Recession Is... Over?, Newsweek, July 14, 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 V.I. Keilis-Borok et al., Pattern of Macroeconomic Indicators Preceding the End of an American Economic Recession. Journal of Pattern Recognition Research, JPRR Vol.3 (1) 2008.

- ↑ Mishkin, Fredric S.. "How Should We Respond to Asset Price Bubbles?" (May 15, 2008). Retrieved on 2009-04-18.

- ↑ Foldvary, Fred E. (September 18, 2007) (PDF). The Depression of 2008. The Gutenberg Press. ISBN 0-9603872-0-X. http://www.foldvary.net/works/dep08.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-04.